The future is in plain sight. You just need to know where to look and pay attention. In 2026, our trend "Sowing Seeds of Doubt" is no longer a prediction; it's the operating environment for anyone in the food and beverage industry. (You can read about it in our 2026 Nourish Trend Report.) Multiple forces are converging—regulation, tech, activism, GLP‑1s, and even packaging copy—and together they're setting up the biggest reformulation wave we've seen in this industry in a generation.

From FOP Labels to Children's Ad Rules, Regulatory Pressure Tightens

Front-of-pack labelling in Canada (and similar moves likely coming in the US) has already pushed manufacturers to quietly reformulate to avoid warning symbols for sugar, sodium, and saturated fat (HFSS foods). Those same nutritional thresholds are now showing up in how food brands can advertise to kids.=

The UK has gone further, turning what North America still treats as "voluntary" or "self‑regulation" into hard law. As of January, a landmark nationwide ban restricts advertising of HFSS foods before 9 pm on TV and online at all times, with products assessed via a nutrient profiling model that can capture not just obvious junk, but also some breakfast cereals, sweetened breads, ready meals and sandwiches. The rules still allow promotion of healthier versions, which the government explicitly hopes will "drive reformulation and innovation," a clear signal that policy is being used as a lever to change formulations, not just media plans.

Reformulation is no longer just about "healthier options"; it's becoming the price of entry to communicate with the next generation of consumers.

MAHA, GLP‑1s, and New Food Guidelines Are Politicizing "Highly Processed"

At the same time, the "ultra‑processed" debate has moved from academic circles into mainstream politics and media. Dietary guidelines in multiple markets, including the US, are also beginning to call out ultra‑processed or "highly processed" foods as a category of concern, moving beyond spotlighting individual ingredients.

Layer on the explosion of GLP‑1s, and consumers are being coached—by doctors, apps, and social media—to watch both calories and processing cues. GLP‑1 users ask, "Is this worth my limited appetite?" and suddenly ingredient lists and levels of processing become proxy signals for "waste" or "value" in every bite.

This is exactly what we meant by "Sowing Seeds of Doubt": consumers are no longer simply doubting sugar or fat; they're doubting the entire system that told them processed, fortified, low‑fat products were "better for you" for decades.

The "Yuka Effect": Consumer Apps as R&D Disruptors

But transparency isn't just coming from governments. It's literally in the palm of the consumer's hand.

The food and cosmetics rating app Yuka now has over 80 million users across 12 countries, with 1 in 3 adults in France and between 22–25 million users in the US alone, and has logged over 8.3 billion product scans. For food products, its 0–100 score blends nutritional quality (60%, based on Nutri‑Score), additives (30%, with "high‑risk" additives hard‑capping scores), and "organic" status (10%), then surfaces simple traffic‑light ratings plus suggested "better" alternatives.

Most importantly, the app has a built‑in "call‑out" feature that lets users ping brands directly when they get poor scores, turning millions of consumers into a distributed R&D feedback loop. The impact is real: French retailer Intermarché reformulated over 900 products and removed 142 additives in direct response to Yuka scores, and an estimated 78% of French manufacturers now factor Yuka ratings into product development and reformulation decisions. Yuka's own data shows that 94% of users put back products with a red rating, and 92% say they've reduced their purchases of ultra‑processed foods since using the app.

In other words, it's not just governments sowing doubt about certain foods; it's code. Legal compliance is no longer sufficient protection when a parallel, independent scoring system can instantly frame your product as "poor" or even "bad" at shelf—and offer a competitor's product as the fix.

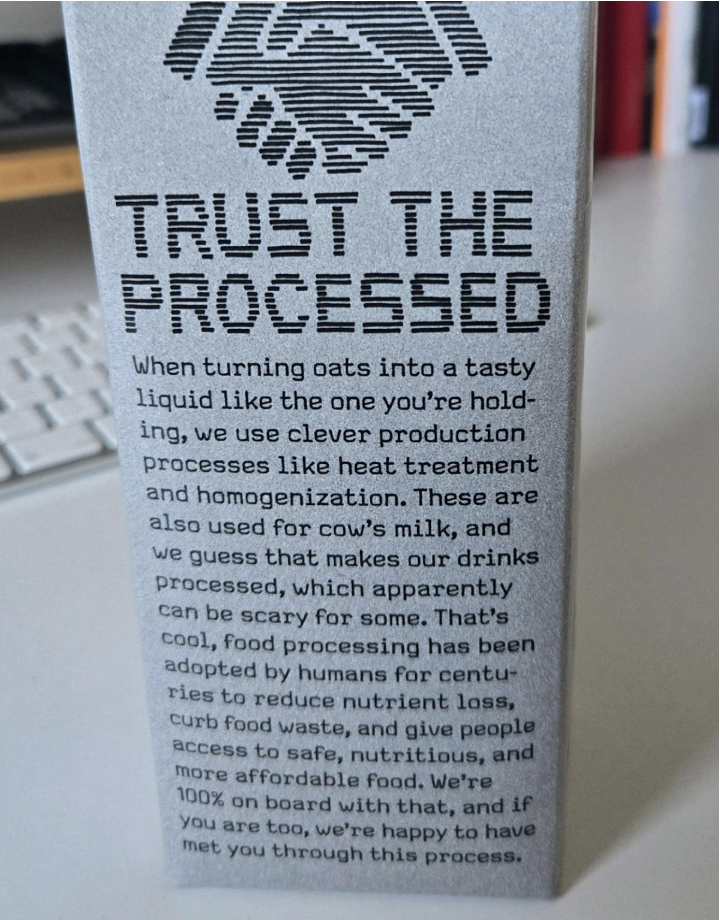

Oatly's "Trust the Processed" Reframes the Narrative, Not Just the Recipe

Against this backdrop, most big brands have stayed quiet on the ultra‑processed debate, hoping not to be tarred with the "UPF = unhealthy" brush. Oatly has decided to do the opposite, and that's worth watching.

On pack, they are explicitly telling consumers to "trust the processed" and using that space to explain how processing can improve food safety, reduce waste, boost affordability, and protect nutrients. Oatly is trying to reframe what consumers should be evaluating: overall nutritional and environmental performance, not an automatic binary assumption that UPFs are bad. It is a rare example of a major FMCG using its packaging as a mini‑masterclass on processing science, and it may be a preview of how brands will have to show up once "processed" becomes as charged as "GMO" was a decade ago.

What This Convergence Means: From Quiet Tweaks to Visible Trade‑offs

When you step back, the pattern is clear. Manufacturers can either defend the old playbook or lead the reformulation. The brands that survive beyond 2026 won't just be the ones with the cleanest labels; they will be the ones that reclaim consumer trust through radical transparency—whether that's by simplifying ingredients or honestly explaining why they use the processes they do.

In a world where doubt is becoming the default setting, reformulation alone won’t be enough. The brands that thrive will be the ones that aren’t trusted merely to have “less” of something, but also, and more importantly, to tell the truth about how food is made in the first place.